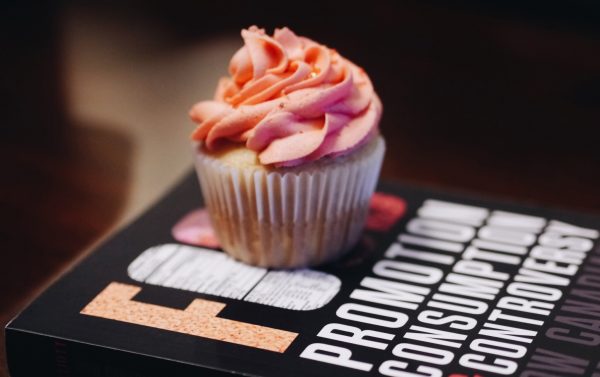

The latest book from AU Press, How Canadians Communicate VI: Food Promotion, Consumption, and Controversy, discusses how food is represented, regulated, and consumed in Canada. Canadians make food choices every day, but a global food system and a growing concern over nutritional value not only makes these choices more difficult, it also means that these choices have far-reaching consequences. This collection of articles examines the values embedded in food advertising, the locavore movement, food tourism, dinner parties, food bank donations, the moral panic surrounding obesity, food crises, and fears about food safety. On the blog today, we are featuring Melanie Rock’s analysis of Kraft Dinner.

Kraft Dinner is a well-known food item in Canadian households and food banks. It is kid food, a guilty pleasure, a symbol of college life, and a great donation item. In her chapter, “Kraft Dinner® Unboxed,” Melanie Rock argues that “the iconic status of Kraft Dinner as a charitable food donation is deeply emblematic of Canadian society, representing cultural practices of eating, sharing, and generosity, but at the same time, it represents an abiding ignorance, and even denial, of deeply ingrained inequity in this country.” The following excerpt from Rock’s chapter raises awareness about how Canadians are communicating about food and what is left out of the conversation.

Kraft Dinner: Tasty, Quick, and Easy to Store? It Depends

Kraft Dinner: Tasty, Quick, and Easy to Store? It Depends

To assist with tracing the social lives of Kraft Dinner, interviews were conducted in 2004 with eighteen food-secure francophone residents of metropolitan Montréal. The sample represented diverse perspectives on and experiences of Kraft Dinner, as the participants ranged in age from early adulthood to senior citizens. Furthermore, the sample included people whose history of employment had involved Kraft Dinner, including someone who had worked on the assembly line in the Montréal factory where Kraft Dinner is boxed and a former product representative for Kraft in the province of Québec. Most of the participants’ work as paid employees, volunteers, or both brought them into direct contact with food-insecure people or encompassed advocacy for social justice.

These interviews brought to light three qualities that make Kraft Dinner seem especially suitable for donation. First, Kraft Dinner has a reputation for being palatable among the eventual recipients. Asked why food donors tend to favour it, one social worker said, “I have the impression it’s [given] because it is seen as a simple product that is well-known.”[i] Another social worker provided a similar explanation. “People still have the impression that working-class people enjoy it,” she said, “despite everything.”[ii] A community activist recalled that her grandmother often prepared Kraft Dinner for her as a child, since she would walk to her grandmother’s house for lunch on schooldays. Later in life, when raising children of her own on a fixed budget, she returned to Kraft Dinner, but as an evening meal toward the end of the week, when she felt tired, and at the end of the month, when money was tight. As another example, a man who worked for a union at the time said, “You might serve it to your own kids, to your own family, or even to yourself. In the end, you make it yourself.”[iii] The association of Kraft Dinner with palatability was especially pronounced in the context of children, thus suggesting that donors are aware of child poverty and are trying to respond sensitively or sensibly when donating Kraft Dinner.

Second, these interviews highlighted the perception that Kraft Dinner is an easy-to-prepare meal in a nutritionally complete package. A lawyer remarked: “It’s easy to prepare and we assume, I suppose that people assume everyone knows how to prepare it.”[iv] An archivist elaborated: “Simply put, there’s the idea of a complete meal, in the sense of protein, pasta. Instead of giving a package of white spaghetti, you give a kit that is a meal.”[v] Later on in the interview, however, this participant pointed out that the cardboard box does not contain any butter or margarine, nor does it contain any milk. In fact, the preparation instructions printed on the cardboard package call for the addition of one to three tablespoons (15 to 45 ml) of either butter or margarine and one-quarter to one-half cup (50 to 100 ml) of fluid milk, depending on whether the traditional or Sensible SolutionTM instructions are to be followed. Yet, repeatedly, the notion of Kraft Dinner as a complete meal in a box was foregrounded in interviews. “You have water [to boil the pasta in]! Butter, margarine, you have these too!” said a college professor.[vi]

Third, these francophone Montréalers emphasized that Kraft Dinner is suitable for donation because this product is safely and conveniently stored. A social worker speculated, “Since it’s not expensive, people will rarely buy just one box. They will buy three or four. So you might buy a case. When you have a case at your house, and people come by for food donations, you have a lot. So why not give even half?”[vii] As highlighted once again in this excerpt, Kraft Dinner would not come to mind or to hand as a food donation if donors did not themselves purchase this product for consumption at some later date. The lawyer cited above had worked his way through law school as a product representative for Kraft, and at the time, he recalled, Kraft Dinner was unusual for containing a dairy product while also having a long shelf-life. This feature of Kraft Dinner made it a popular order in rural areas as well as for supermarkets and smaller neighbourhood-based stores in urban areas. The participants consistently stressed that food banks discouraged donations of goods that are perishable. Implicit here was that the time between donation and consumption was unknown and that the ultimate recipients were also unknown. Giving away a box (or two, or even ten) of Kraft Dinner did not appear to be too much of a sacrifice, and donors may have felt reassured that their gestures of solidarity would ultimately reach and be appreciated by recipients.[viii]

Yet the views of the recipients themselves engendered a very different set of perceptions. Low-income mothers have plainly said that the properties of Kraft Dinner described by the francophone Montréalers cited above do not hold true in their particular circumstances, because they rarely have enough money to last until the next cheque.[ix] And milk, which is needed to prepare Kraft Dinner according to the instructions and for the sake of nutrition and palatability, is strictly rationed yet often lacking in households headed by low-income mothers (McIntyre et al. 2002; McIntyre et al. 2003; McIntyre, Officer, and Robinson 2003; McIntyre, Tarasuk, and Li 2007; McIntyre, Williams, and Glanville 2007; Williams, McIntyre, and Glanville 2010).

Kraft Dinner: Just Add Milk—If You Have It

Kraft Dinner: Just Add Milk—If You Have It

Advertisements, websites, and over fifteen hundred items that originally appeared in English-language newspapers from across Canada were examined as part of inquiring into the social lives of Kraft Dinner. Of these, 155 mention food banks explicitly. Therein, attention tends to focus on the donors, and the tone is often celebratory, with an emphasis on civic generosity. Much of this coverage resonates with the themes drawn out from the interviews with francophone Montréalers and outlined above.

On occasion, the media coverage hints at the fact that Kraft Dinner forms part of a monotonous diet for low-income Canadians, whether or not they receive charitable food assistance, and at the fact that receipt of food charity can feel stigmatizing: for example, a newspaper article reported, “The Ryders don’t use the local food bank. When asked how they feed a family of five on their limited income, Travis responded, ‘We eat a lot of Kraft Dinner.’”

The newspaper quotation that best resonates with what low-income mothers have reported about Kraft Dinner is the following: “A 42-year-old single mother of three . . . makes the rounds of alleys at night scrounging for returnable bottles so she can buy milk for her kids. . . . The children eat a lot of watered-down Kraft dinners ‘but they don’t complain as long as it fills them up,’ she said.” In fact, Canadian newspapers rarely report on the extent to which socioeconomic circumstances and policies from multiple sectors and levels of government exert influence on population health. Canadian reporters and editors face numerous challenges when seeking to convey stories of this nature (Gasher et al. 2007). Out of a sample of 4,732 items originally published in Canadian daily newspapers, Hayes and colleagues (2007) found only nine items that deal with income as an influence on human health.

In light of the paucity of media coverage on poverty as a cause of ill health and the tendency for Canadian media to emphasize how those who are food-secure experience Kraft Dinner, even in stories about food insecurity, I initiated media advocacy (Wallack and Dorfman 1996). An experienced media relations specialist developed a comprehensive strategy that included a news release in print and video formats. The key messages were that poverty is a public health problem, that millions of Canadians live with food insecurity, and that ignorance of poverty exists in mainstream culture. A news conference took place to facilitate interviews with reporters. The resulting coverage included online bulletins, radio interviews, and television stories on regional and national broadcasts, all highlighting that food-insecure Canadians are often obliged to eat Kraft Dinner prepared without milk because they have run out of money for food. The media advocacy encouraged donating money to food banks instead of boxes of Kraft Dinner, but it also stressed that charitable donations cannot prevent food insecurity from occurring. In sum, however compassionate the intent, the popularity of Kraft Dinner donations to food banks was presented as indicative of widespread misinformation about poverty and ill health in the Canadian population.

Overall, responses to the media advocacy illustrated the symbolic potency of Kraft Dinner in Canada. For example, consider the following response, which was posted to the website for CBC.ca: “This story informed me that my best intentions, while good, are misguided. I will be looking up what my local food bank needs before blindly donating next time.” A few posts referred to donating money instead of packaged foods. As one citizen wrote on the CBC.ca website, “When I donate to the food bank, I do it as cash. Hopefully then the food bank will buy real food for those in need.”

The advocacy messages about the advantages of donating money rather than packaged foods such as Kraft Dinner were facilitated by the involvement of James McAra, the chief executive officer of the Calgary Food Bank. He explained that his organization could redistribute more than four dollars’ worth of food for every dollar received. (That ratio has since increased to 5 to 1 [McAra, pers. comm., 1 March 2013].) Prior to becoming involved in repurposing Kraft Dinner for media advocacy, I had never considered that a food bank might negotiate directly with industry suppliers. Moreover, the Calgary Food Bank uses cash donations to purchase fluid milk and other perishable items for redistribution to households and community-based agencies.

Vitriolic responses were posted online, too: for example, “If the food bank recipients don’t like it or think we are just emptying out our cupboards, then I say, ‘Hey Dude/Dudette: GET A JOB.’” Yet many people experiencing food insecurity in Canada do, in fact, work for pay (McIntyre, Bartoo, and Emery 2014; Persaud, McIntyre, and Milaney 2010). The Calgary Food Bank reports that 38 percent of clients who accessed the Food Bank from 1 September 2013 through 31 August 2014 had at least one employed person in the household.[x]

Suspicion was also expressed about social research in several online responses, including this one: “What I would like to know is: a) How this study could possibly help the people in question? and b) How many needy families could have been fed with money wasted on this study?” Resistance to the messages on linkages between poverty and ill health had been anticipated, albeit in a general way, but suggestions that social research itself might be seen as a poor investment were unexpected.

References

Gasher, Mike, Michael V. Hayes, Ian Ross, Robert A. Hackett, Donald Gutstein, and James R. Dunn. 2007. “Spreading the News: Social Determinants of Health Reportage in Canadian Daily Newspapers.” Canadian Journal of Communication 32 (3): 557–74.

Hayes, Michael, Ian E. Ross, Mike Gasher, Donald Gutstein, James R. Dunn, and Robert A. Hackett. 2007. “Telling Stories: News Media, Health Literacy and Public Policy in Canada.” Social Science and Medicine 64 (9): 1842–52.

McIntyre, Lynn, Aaron C. Bartoo, and J. C. Herbert Emery. 2014. “When Working Is Not Enough: Food Insecurity in the Canadian Labour Force.” Public Health Nutrition 17 (1): 49–57.

McIntyre, Lynn, N. Theresa Glanville, Suzanne Officer, Bonnie Anderson, Kim D. Raine, and Jutta B. Dayle. 2002. “Food Insecurity of Low-Income Lone Mothers and Their Children in Atlantic Canada.” Canadian Journal of Public Health 93 (6): 411–15.

McIntyre, Lynn, N. Theresa Glanville, Kim D. Raine, Jutta B. Dayle, Bonnie Anderson, and Noreen Battaglia. 2003. “Do Low-Income Lone Mothers Compromise Their Nutrition to Feed Their Children?” Canadian Medical Association Journal 168 (6): 686–91.

McIntyre, Lynn, Suzanne Officer, and Lynne M. Robinson. 2003. “Feeling Poor: The Felt Experience of Low-Income Lone Mothers.” Affilia: Journal of Women and Social Work 18 (3): 316–31.

McIntyre, Lynn, Valerie Tarasuk, and Jinguang Li. 2007. “Improving the Nutritional Status of Food-Insecure Women: First, Let Them Eat What They Like.” Public Health Nutrition 10 (11): 1288–98.

McIntyre, Lynn, Patricia Williams, and N. Theresa Glanville. 2007. “Milk as Metaphor: Low Income Lone Mothers’ Characterization of Their Challenges in Acquiring Milk for Their Families.” Ecology of Food and Nutrition 46: 263–79.

Miller, Daniel. 1998. A Theory of Shopping. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Persaud, Steven, Lynn McIntyre, and Katrina Milaney. 2010. “Working Homeless Men in Calgary, Canada: Hegemony and Identity.” Human Organization 69 (4): 343–51.

Prainsack, Barbara, and Alena Buyx. 2012. “Solidarity in Contemporary Bioethics: Towards a New Approach.” Bioethics 26 (7): 343–50.

Rock, Melanie J., Lynn McIntyre, and Krista Rondeau. 2009. “Discomforting Comfort Food: Stirring the Pot on Kraft Dinner® and Social Inequality in Canada.” Agriculture and Human Values 27 (3): 167–76.

Wallack, Lawrence, and Lori Dorfman. 1996. “Media Advocacy: A Strategy for Advancing Policy and Promoting Health.” Health Education Quarterly 23 (3): 293–317.

Williams, Patricia L., Lynn McIntyre, and N. Theresa Glanville. 2010. “Milk Insecurity: Accounts of a Food Insecurity Phenomenon in Canada and Its Relation to Public Policy.” Journal of Hunger and Environmental Nutrition 5 (2): 142–57.

Notes

[i] “C’est parce que j’ai l’impression que ça correspond à un produit simple, qui est connu.”

[ii] “On a vraiment la perception que c’est aimé dans les couches populaires, en fait, je pense que c’est une perception que c’est aimé, le Kraft Dinner, malgré tout.”

[iii] “Tu peux en servir à tes enfants, à ta famille, ou même t’en servir pour toi-même, c’est que dans le fonds, tu le prépares toi-même.”

[iv] “C’est facile à préparer et on présume, je suppose qu’on présume que tout le monde sait comment le préparer.”

[v] “Simplement, l’idée repas complet, dans le sens protéines, pâtes. Au lieu de donner un paquet de spaghettis blancs, tu donnes le kit, qui est un repas.”

[vi] “On a de l’eau! Le beurre, la margarine, t’en as!”

[vii] “Comme c’est pas cher, c’est rare que les gens vont acheter une boîte. Ils vont en acheter trois à quatre, donc … faique t’achètes une caisse. Quand t’en as une caisse chez toi, pis que les gens passent pour le magasin partage t’en as beaucoup fait que … pourquoi pas en donner peut-être même la moitié, tsé?”

[viii] While an in-depth application of the concept of solidarity lies beyond the scope of this chapter, the term is used advisedly here, to mark individual and collective responses to the needs of others (Prainsack and Buyx 2012).

[ix] This data comes from a secondary analysis of individual interviews and focus groups conducted for research led by Lynn McIntyre (see Rock, McIntyre, and Rondeau 2009).

[x] “Fast Facts,” Calgary Food Bank, 2015, http://www.calgaryfoodbank.com/fastfacts.