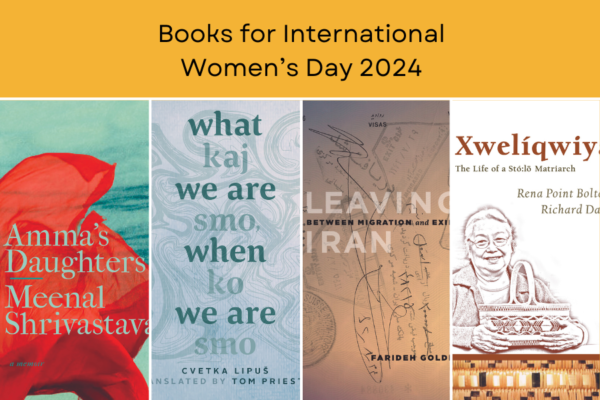

Fearful of losing her family’s history and her father’s memories about Jewish life during World War II in Iran, Farideh Goldin asked Baba, as she called her father, to write his story. When he handed her his memoir, she was surprised to find that he had filled his notebook with the story of his last years in Iran following the 1979 Revolution. He documented the years he spent trapped in the country he loved, separated from his wife and children and revealed stories of pain and hardships that had previously been unknown to his family.[inlinetweet prefix=”null” tweeter=”null” suffix=”null”] In Leaving Iran, Farideh Goldin explores her role in Baba’s life alongside his recounted experiences.[/inlinetweet]

The following excerpt is the beginning of Baba’s journey—his arrival in Israel during the Revolution. But the Promised Land is not as Baba had imagined.

September 1980, Tel Aviv

My lungs burned as I struggled to inhale the humid, exhaust-filled air of Tel Aviv. It had been five months since my family’s rushed exodus from Iran amidst a revolution that turned our lives upside down, and I was still lost, sleepless, dazed. I missed Shiraz, the crisp, dry breeze sweeping down from the mountains to the valley that had been home to my ancestors for thousands of years. Exiled to Babylon after the destruction of the First Temple in Jerusalem, my people were set free in 539 BCE by the Persian King, Cyrus the Great, and they followed him to Persia. Like my forefathers, I had prayed for a return to Zion every holiday, every Shabbat, every day. At the end of each Passover Seder, I would say wholeheartedly, “Next year in Jerusalem!” But now that I was finally in the Holy Land, I yearned to return to Iran.

I struggled to inhale the humid, exhaust-filled air of Tel Aviv. It had been five months since my family’s rushed exodus from Iran amidst a revolution that turned our lives upside down, and I was still lost, sleepless, dazed. I missed Shiraz, the crisp, dry breeze sweeping down from the mountains to the valley that had been home to my ancestors for thousands of years. Exiled to Babylon after the destruction of the First Temple in Jerusalem, my people were set free in 539 BCE by the Persian King, Cyrus the Great, and they followed him to Persia. Like my forefathers, I had prayed for a return to Zion every holiday, every Shabbat, every day. At the end of each Passover Seder, I would say wholeheartedly, “Next year in Jerusalem!” But now that I was finally in the Holy Land, I yearned to return to Iran.

I walked along the narrow alleyways of Takhanat Merkazeet, the central bus terminal in Tel Aviv, where time had stopped and modernity didn’t dare encroach. Travellers tried to find their connections in the winding, confusing maze of alleyways that were lined with small shops. Shoes, bolts of fabric, and household knick-knacks filled the small shops and poured onto the sidewalk. The shopkeepers sat uncomfortably on metal chairs or low stools, chatting with each other or with the familiar faces in the crowd. The smell of falafel, kebab, herb polo, and freshly squeezed juices—orange, pomegranate, carrot—blended with the pungent odour of Noblesse and Marlboro. I reached into my shirt pocket for a cigarette, the last of a pack I had brought from Iran, and held it between my fingers, but resisted lighting it.

Avateeachhhhh, tut sadeh, vendors yelled, watermelon, strawberries. My little daughter Niloufar loved strawberries—a new, exotic fruit for her.

Waiting for buses to take them to the beaches or to Jerusalem for sightseeing, tourists chatted in languages unfamiliar to my ears. Their exuberance stood in stark contrast to the gloom hanging over the refugees whose language I understood, whose pain I shared. We didn’t laugh or bargain at the gift stores or linger at the cafes. We looked haggard; we had withdrawn to a deep pain within.

My name is Esghel Dayanim, the son of Mola Meir Moshe Dayanim, the chief rabbi and judge of the Jewish community of Shiraz, a holy man, like his fathers for many generations, revered by Jews as well as many Muslims. Now I am an avareh, a wanderer.

Read the rest of the book here.