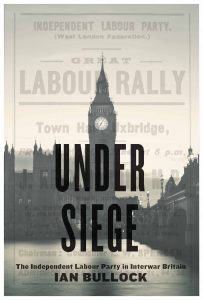

Ian Bullock’s latest book, Under Siege: The Independent Labour Party in Interwar Britain examines the ideological battles within the Independent Labour Party during the tumultuous interwar period. By combing through newspapers, leaflets, and party documents, Bullock arrives at a detailed explanation of the most controversial and significant debates of the period, and includes some, like the Living Wage policy, that continue to bear contemporary relevance.

The following excerpt is an overview of the sieges that the ILP found itself battling in the years before the Second World War.

Under Siege

Like any political organization, and perhaps more than most, the ILP was never quite “one thing” at any point in its history. In the period in question, its stance and its leadership, as well as its size and potential political influence, was almost continually changing from the end of the First World War in the final weeks of 1918 to the outbreak of the Second in the late summer of 1939. One of its most prominent early leaders, Philip Snowden, was already showing definite signs of disenchantment with the party by 1920. This was reinforced after the critical reactions of many in the party, as well as elsewhere on the Left, to his wife Ethel’s outspoken criticisms of the Bolsheviks after her visit that year to Russia with the Labour Party delegation.[1] Rapid change and, especially after disaffiliation in 1932, internal controversy, would continue for the rest of the interwar years.

It could plausibly be argued that by 1939, the ILP was an entirely different sort of organization than the one that had operated twenty years previously. In the early 1920s, it was still the main route for individuals to become members of the Labour Party and was therefore still part of the political mainstream. Its position in this respect was already threatened, and seen to be threatened, by the provision in the new Labour Party constitution for individual party membership in local branches. Twenty years later, the ILP was a much smaller entity on the political fringe, yet there were also continuities. It was throughout—in spite of all its diversions, crosscurrents, and contradictions—a residuary legatee of the pre-Leninist radical democratic currents of the Left, including guild socialism, with its emphasis on workplace democracy.

It is an almost universal judgment that the 1932 disaffiliation was a huge mistake. It is difficult to find any grounds on which to disagree. Many in the ILP itself had already reached the same conclusion by 1939. Only the outbreak of war prevented the holding of a special conference to decide whether to follow the NAC’s recommendation to seek reaffiliation. Peter Thwaites pinpoints the choices and the consequences for the ILP when it decided not to go ahead with this in his thesis on the ILP between 1938 and 1950:

When the ILP hesitated on the brink and then took a step back from reaffiliation to the Labour Party in 1939 it unwittingly doomed itself to virtual extinction. Inside the Labour Party the ILP might have replaced or united with the infant Tribune Group to become the voice of the Labour Left. Or it might have become submerged within the mass party within a short time and ceased to be a coherent group, but at least the individual ILPers would have been in contact with the mass of the labour movement and they might have been able to exert an influence, no matter how small, on the direction the Labour Party took.[2]

The danger of being submerged in the Labour Party and thereby losing its radical identity was one side of the siege that the ILP experienced—mainly from forces within it and in the minds of its members—throughout the interwar period. On the other side, the besiegers were the ideas and emotions drawing the party either into a merger with the Communist Party of Great Britain or towards trying to set itself up as its own version of a Bolshevik-style revolutionary party in a context where there was little sign of revolution.

Read the entire book on our website.

[1] Keith Laybourn, Philip Snowden: A Biography, 1864–1937 (Aldershot, UK: Temple Smith, 1988), 86; Ian Bullock, Romancing the Revolution: The Myth of Soviet Democracy and the British Left (Edmonton: Athabasca University Press, 2011), 202–5.

[2] Peter James Thwaites, “The Independent Labour Party, 1938–50,” PhD diss., London School of Economics, 1976.

Image by Mайкл Гиммельфарб (Mike Gimelfarb) – Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5049123