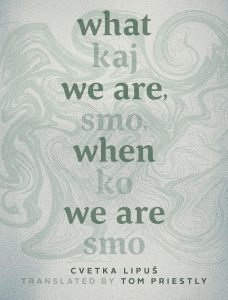

In 2014, Meytal Radzinski, a young scholar, founded Women in Translation Month to be held annually in August in response to the gender disparity she noticed in works of translation. Radzinski’s goal was to encourage people to read more books by women in translation and increase awareness about the gender disparity in the field. Since 2014, she has collected yearly statistics on the publication of women in translation, requested statements from publishers on their lack of works by women in translation, published countless reading lists, and advocated tirelessly for more attention to be paid to this matter. Athabasca University Press has published a few women in translation over the years—short stories from Odisha, India, a novel from Poland—and next month, we will be publishing the translation of Cvetka Lipuš’s Kaj smo, ko smo (What We Are When We Are), an award-winning book of Slovenian poetry.

Why is translation so important?

In her foreword to What We Are When We Are, Donna Kane reflects on the importance of translation, “Each time I read a translated poem, an image, a thought, a perspective, once hidden from me, is revealed. I am given a new experience, a chance to widen the scope of my perceptions. Sometimes that new perspective is a recognition that, regardless of language and culture, we share many of the same root concerns and questions. Seeing the familiar in the strange is not only a comfort but expands the gift of empathy.”

In her foreword to What We Are When We Are, Donna Kane reflects on the importance of translation, “Each time I read a translated poem, an image, a thought, a perspective, once hidden from me, is revealed. I am given a new experience, a chance to widen the scope of my perceptions. Sometimes that new perspective is a recognition that, regardless of language and culture, we share many of the same root concerns and questions. Seeing the familiar in the strange is not only a comfort but expands the gift of empathy.”

Translated into English by Tom Priestly, these poems blend the real with the surreal, dull urban lives with dreams. Lipuš, known for the lexical beauty of her work, dwells on topics of time and space which she handles in an almost revolving, irreverent manner. Priestly captures the maze-like characteristic of her verse and carefully reconstructs the sonoric beauty of the work into What We Are When We Are. The first proofs have arrived just in time to share a sneak peek for Women in Translation Month. The Slovenian and English versions will printed on facing pages as reflections of each other.

Regrets

If you were to change the clock

as we do in the fall, when we move

the clock’s hand back,

would you steer through yourself

by the heavenly map of your ancestors,

past grandmothers and grandfathers,

who with advice and warnings

indicate the navigational path,

along which sail your descendants

under the flag “who flies high,

falls low”—

in greater and greater numbers.

Or would you rather let go of the angel’s

elbow and jump,

jump.

Employment

Ads have been pulled, but the sky continues to invite into

its ranks a specialist, male or female, in the production of clouds.

Given the increase in the scope of the work, it seeks an inventive

and skilful person to multiply the number of clouds without

triggering showers or storms. As well as technical know-how

we expect good communication skills and outstanding

negotiating abilities. You will have to convince customers

who for millennia have been concluding their holy business

from the refuge of crystal armchairs that in future they will have to

share their space. How you will persuade them of the necessity

of expansion is left to your own judgement. If they should refer to higher

authority, you may on your own initiative and without witnesses threaten them

with having their wings clipped. We presuppose an excellent knowledge of the language

of the winds and the dialect of heavenly directions, and at least a basic

comprehension of Old Hebrew. Are you ambitious, did you ever put

fireflies into jars, and are you unafraid of heights? Address

your application to the heavens with the subject line “cloud.”

To-Do List

First thing in the morning I check you off the list,

as you are still asleep. Together the sun and I

make our rounds, we add up the streets in our district,

I subtract the one with the dog. During the meeting,

engrossed in a game of Battleships, when someone says “A 4”

the project goes belly-up. After lunch I throw in

the towel, so that all afternoon I am counting

the threads and strands. On the way home

I pop into the store for merchandise into which

I put my efforts. My legs find their way into

a nearby bar: there people I know

balance up the empty years and the full

glasses into an odd number. When I get back,

you are half asleep. Drowsily you look over

your own list and cross me off.