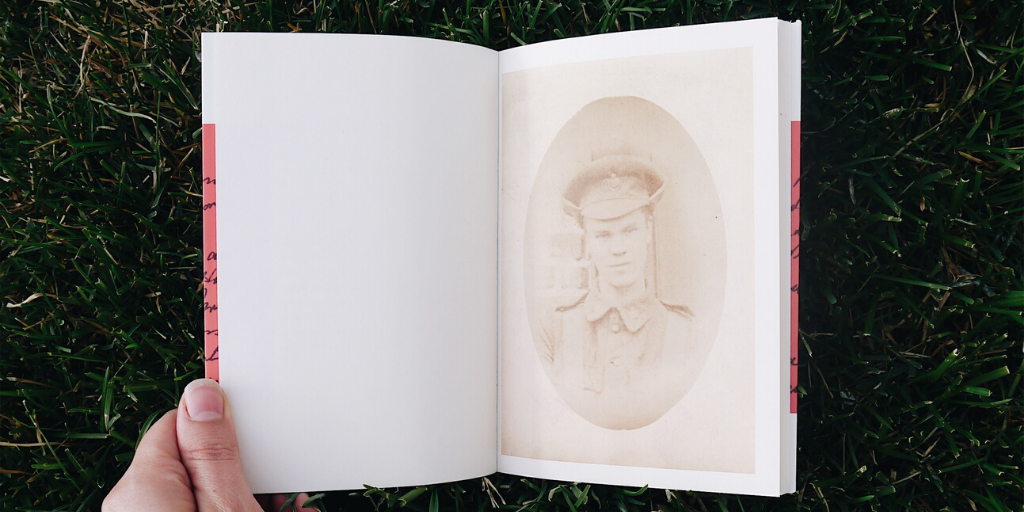

This year, the world marked 100 years since the signing of the Treaty of Versailles—the peace agreement that officially ended the First World War. As we move further away from that historical moment, it becomes more difficult to remember the individuals who fought and died in that conflict. Perhaps what we need now is an unforgetting more than a remembrance.

In Unforgetting Private Charles Smith, Canadian poet and academic, Jonathan Locke Hart urges us to consider the life of a single soldier. Hart discovered Charles Smith’s diary from the First World War in the Toronto Reference Library and was struck by a voice full of life, and the presence of a rhythm, a cadence that urged him to bring forth the poetry in Smith’s words. From the fragments of information about this ordinary man’s life, Hart creates a legacy for Smith by setting the words of the young soldier’s diary in poetic form. Accompanying this poetry is a poignant essay describing how Hart pieced together a forgotten soldier’s story. A story that ended June 1916 in the Battle of Mount Sorrel.

Today, in honour of Remembrance Day, we are sharing an excerpt from Hart’s essay on unforgetting.

When I first met him, Private Charles Smith had been dead for close to a century. I no longer remember precisely when I came across his small diary in the Baldwin Collection of Canadiana at the Toronto Reference Library. With its dark plastic cover and metal ring binding, it is an unremarkable object—every bit as nondescript as its author’s name. The entries begin on 5 June 1915; the final one is dated 31 May 1916. Eleven months or so of Smith’s life, pinned to the lined pages, without past or future.

[…]

At first, I had no information about him other than what appeared in the diary itself: “Chas. Smith # McG173 3rd Company Princess Patricia Light Inftry. British Expeditionary Force.” And, above the first entry: “Sworn in 5th June 1915.” Evidently, then, Smith had received training through the McGill University contingent of the Canadian Officers’ Training Corps and had subsequently been sent overseas as a member of the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry. At the front of the diary, Smith had written:

Please return to

Mrs. E. E. Smith

16 Geneve Ave

Toronto

Was “Mrs. E. E. Smith” his mother? Some other relative? I did not know. Only slowly did my unforgetting take shape. The first detailed entry is dated Monday, 28 June 1915: “Not much to do today. Had most of the day off. Paraded at 7 p.m. in full marching order. Left Parade Grounds 7:30 bound for boat. Got a good send off. Sailing on S.S. Northland.” The diary continues in the same matter-of-fact style. “Was on duty all last Night. Today whilst on lookout 3 bullets struck the chimney just behind me. Weather fine & cool.” “Tramp. Weather hot in Day rain at Night.” Smith was not writing to express himself—to record his thoughts, his emotions, his opinions. He was simply writing down what happened, in telegraphic style.

As part of my historical research, I decided to transcribe his diary. In the age of digital scanning, this might seem a peculiar choice, and yet the very laboriousness of the process obliged me to focus my attention on the words I was copying. I continued my work for some time, whenever I visited the Toronto Reference Library, engaging in my own form of archiving, almost like a ritual of remembrance. The voice was his own, full of life—a man in the trenches asserting the individuality of his experience in the vastness and inhumanity of the war. As I transcribed his words, I gradually became alert to their rhythm and cadence, and I found myself wanting to bring forth the poetry I was hearing. As usual, words imprint themselves on me, forming patterns, and a poem begins. In some ways, this poem came fast, as I was merely the scribe to Smith’s muse, arranging the score of his composition.

[…]

When I created a poem from the words in Smith’s diary, I did so mostly for myself. It was my way of internalizing his experience. I did not set out to appropriate the prosaic words of an ordinary soldier and elevate them to status of poetry. There was no need: they were already poetry, although perhaps with one exception. Poets—by which I mean people who think of themselves as poets—write with readers in mind and craft their words accordingly. They have one eye on their literary reputation. Whatever else, Smith almost certainly did not conceive of his diary as literature.

Quite possibly, this was private writing, a putting of words on paper with no expectation that someone else would one day read them. Perhaps Smith silently hoped that he would return from the war and that these staccato words would someday serve as an aide-mémoire, notes from which stories could then be elaborated. It is a reassuring vision. Then again, whether consciously or not, Smith may have been writing for his mother and father, and possibly for his siblings, if he had any. “Please return to Mrs. E. E. Smith.” The request says so much. Perhaps Smith was creating his own memorial, something for his parents to cherish after he was gone—something that, as it turned out, would have to stand in place of his body. He wanted the diary to survive, even if he did not. This could be why he did not speak of his emotions: perhaps he felt that such accounts would be too painful to read. Or to write. Perhaps he could live only by immersing himself in the mundane and immediate and concrete.

To continue reading, head over to our website and download the entire book for free.