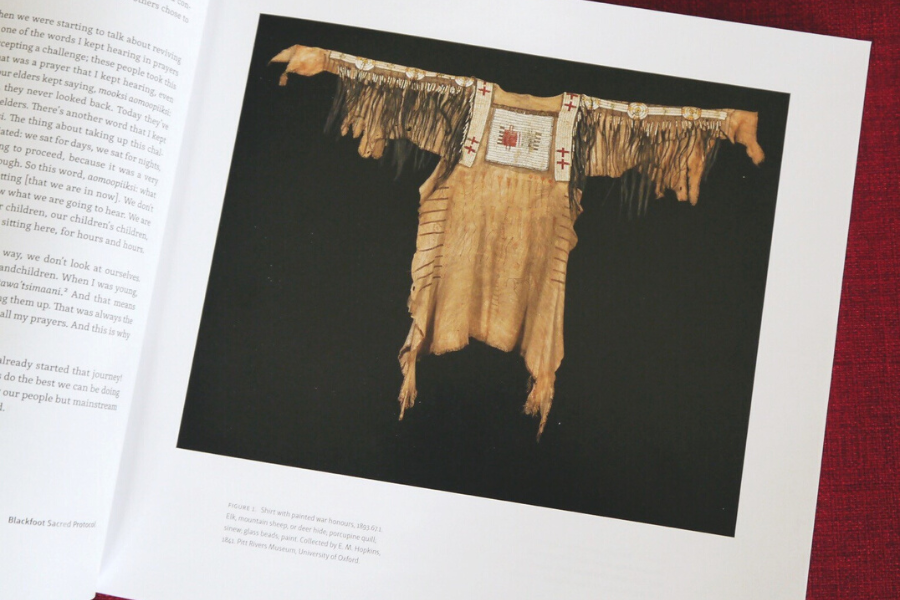

The work of repatriation has been ongoing for many decades and there have been a number of success stories, but many items belonging to Indigenous communities are still held captive in museums around the world. Some recent projects were delayed by the Covid-19 pandemic, but now that restrictions are starting to lift, important work is beginning to move forward. For example, Chief Crowfoot’s hairlock shirt and buckskin leggings were returned just last month after spending over a century in the Royal Albert Memorial Museum and Art Gallery in Exeter, England. A collection of Mi’kmaw items will be on loan to the Mi’kmawey Debert Cultural Centre in Halifax from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. Additionally, a recent delegation to the Vatican opened up the possibility of the repatriation of many items currently housed there, but no concrete steps were taken and the process could take years.

It’s not just museums abroad holding on to items that rightfully belong to Indigenous communities. Many Canadian museum collections contain artifacts that can and should be repatriated. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action include a call to the federal government to “provide funding to the Canadian Museums Association to undertake, in collaboration with Aboriginal peoples, a national review of museum policies and best practices to determine the level of compliance with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and to make recommendations” (67). For reference, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Article 11.1 states “Indigenous peoples have the right to practise and revitalize their cultural traditions and customs. This includes the right to maintain, protect and develop the past, present and future manifestations of their cultures, such as archaeological and historical sites, artefacts, designs, ceremonies, technologies and visual and performing arts and literature.” Article 12.2 states “States shall seek to enable the access and/or repatriation of ceremonial objects and human remains in their possession through fair, transparent and effective mechanisms developed in conjunction with indigenous peoples concerned.”

Some Canadian museums have taken steps toward repatriating some of their collections but the process can be slow and filled with delays. The Royal BC Museum has been working with the Huu-ay-aht First Nations but the Nuxalk First Nation is still waiting for a family totem pole to be returned and the Tseshaht First Nation has called for a reallocation of funds to repatriation efforts from the museum’s recently announced upgrade budget. The Canadian federal government has taken some steps toward answering the TRC’s repatriation call to action, but more could be done by both government and individual museums. To learn more about the repatriation process, check out the resources below.

![[book cover] Visiting with the Ancestors](https://www.aupress.ca/app/uploads/120249_Visiting-with-the-Ancestors-cover.jpg)